MITCH TO THE MED AND BACK PART 3 - BISCAY, the GIRONDE AND CANALS, 2019

- Jul 26, 2022

- 16 min read

Updated: Jul 27, 2022

The boatyard at Foleux was a little bit grim in March 2019 when we returned by car to work on Mitch. It rained for a lot of the time, and our accommodation, a two star hotel on the retail park in Redon, left something to be desired. We completely emptied the main fuel tank, and carefully cleaned it out. We removed the propeller which had been damaged during our grounding in the Vilaine estuary, we fondly imagined by hitting a cannon dumped overboard by a French warship desperately trying to get into the Vilaine to escape Hawke’s squadron, but it was in reality more likely to have been a rock.

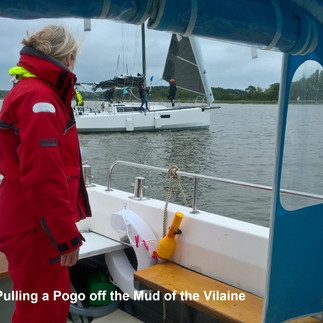

Things were slightly more cheerful when we came back in late April. We stayed in a nearby gite, and worked steadily on the boat. The climate of the Vilaine seems to encourage the growth of mould, and Sally expended considerable energy wielding the pressure washer. We launched the boat, and put it in the marina. On 28th April 2019 we left the marina, bought diesel at Arzal, and went through the lock. After pulling a Pogo yacht off a mudbank, we picked up a mooring and spent a rather cold and rainy night opposite Treghuir, near the mouth of the Vilaine. We were under way by 0630 the following morning, and had a rather rough passage to Port Joinville, on the Ile d’Yeu, where we stayed in the marina. The Ile d’Yeu is extremely picturesque, with development kept under control, and we realised when we went ashore that we had left Brittany, and were in Vendee. The cars seem to be deliberately, perhaps ostentatiously scruffy with a high proportion of Deux Chevaux and Renault 4s We rented bicycles near the ferry port, and rode to a beach at the southern end of the island.

Next day, 30th April, the weather was glorious. We bought some ridiculously expensive fuel and, after diagnosing an autopilot problem (I had inadvertently switched the hydraulic pump off), set out at steady 12 knots on a trip so perfect that I think I will always remember it. South-east across a calm and blue Bay of Biscay, past Sables d’Olonne where huge racing yachts were practicing, before sweeping into the Pertuis Breton, with the Ile de Re close on the starboard side, and the Re Bridge steadily increasing until we were under it, past a tanker discharging at La Pallice and across the Basque Roads, so redolent of naval history, to the Ile d’Oleron.

We followed a fishing boat into the marina at St Denis, and went ashore for a rather sparse dinner, and back aboard for a top up. St Denis was chiefly notable for the number of Jeanneau Merry Fisher boats in the marina, literally acres of them.

The St Denis marina is tidal, so we left early the next morning and picked up a mooring just outside to wait so that we would have favourable tidal conditions for entering the Gironde. I have a great deal of respect for the Gironde entrance, as I was once in a 20,000 ton BP Tanker which had to wait for the weather to moderate for two days before attempting the passage. We went north round the Ile d’Oleron, through the Pertuis d’ Antioch, rather than taking the shallow Pertuis Maumasson at the southern end. The 30 mile trip south was smooth, although there was a significant swell. Cadouan lighthouse emerged from the haze, and we turned to port at the Grande Passe de l’Ouest fairway buoy. In the channel, despite the windless conditions and nominally flooding tide, the swells steepened quite alarmingly, the boat surfing down them with the bow wave level with the foredeck, while I kept a lookout astern for any breakers.

We had intended to stop at Royan, but the boat was going so well that we continued up the Gironde, past our first wine chateau, and to the town of Paulliac, where we had our first encounter with river cruise ships. The marina at Paulliac is swept by the tides of the Gironde, and we picked up a buoy until slack water, anxiously watching the seemingly rather inept manoeuvrings of a river cruise ship attempting to come alongside the quay. We had dinner ashore, our first experience of ordering the vegetarian option in a French restaurant. In the morning we visited the informative Office de Tourisime, had a wine tasting at Rose Paulliac, followed by a wonderful walk through the vineyards around Chateau Rothschild.

Our night was slightly disturbed by an altercation aboard a Viking river cruise ship, and the police were in attendance when we left Paulliac marina at seven on 2nd May, the water, almost like liquid mud, sluicing impressively under the quay. We picked up a mooring to await what we thought would be the optimum time for carrying the tide up the Gironde, and set off upstream at 1100. The trip up the Gironde and Garonne was utterly wonderful, though the tide unexpectedly headed us all the way. Going through the busy city of Bordeaux by boat was a tremendous experience, even if the arched Pont St Pierre gave us some anxious moments with Mitch having to call on considerable reserves of power to get up the standing wave under it.

The Garonne, with its fast muddy flow and astonishing towns, villages and chateaux, was truly wonderful, and it was with a feeling of having had a unique experience that at eight in the evening we tied up at the waiting pontoon outside the Ecluse de Castets.

I think that the trip up the Garonne must have been the most wonderful eight hours I have ever spent on a boat. We went ashore and reconnoitred the lock, ascertaining its opening times. The night was disturbed by the numerous otters who seemed to amuse themselves by jumping noisily off the pontoon into the river.

In the morning, Sally went ashore to communicate with the eclusier, and I took the boat into the lock, which is fitted with floating bollards. We tied up briefly while a VNF vignette was acquired. This was Mitch’s entrance into the French Canal system, and it would be three years before he would return to his natural, tidal element.

The Garonne Canal was built as an extension of the much earlier Canal du Midi. It bypasses the Garonne river, whose strong currents and shoals made navigation difficult, and enabled canal navigation from the Atlantic to the Mediterranean. Its completion in 1856 almost coincided with the opening of the Bordeaux to Sete Railway by the Compagnie des chemins de fer du Midi. Ownership of the canal passed to the railway company, which was reluctant to fund the canal which competed with their expensive asset. Nevertheless, the canal is a wonderful exercise in straightforward, confident Victorian engineering, and to my mind is extremely attractive, passing through unspoiled towns and villages.

The locks on the Garonne canal are automatic, the sequence initiated by twisting a rod dangling from a wire spanning the canal. We knew this intellectually, but completely failed to recognise the rod on our approach to the lock. After a bit of scrambling about, we realised our mistake, and the lock operated without any problems. The Garonne canal is a lateral waterway, rather than a summit canal, and it is uphill all the way to Toulouse. This means that the locks were always empty when we entered them. The abundance of water flowing into the canal from the Garonne river means that the spillway channels beside the locks often provoke strong cross currents in the lock entrances. Our practice was to stop briefly at the landing stages provided, and for Sally to go ashore and stand by the lock. When she was in position, I twisted the rod to initiate the sequence, and when the light on the lock showed green, I took the boat into the canal and threw the lines up to her. When the boat was fast, she pressed the operating button, and the filling sequence began. As Mitch lifted, Sally rejoined, and we let go the lines and pushed off when the lock gates opened.

On our first day on the canals progressed, we began to get the hang of the locks, but it was tiring work, and we were glad to stop about five in the evening, near Lock 47, having negotiated six locks and travelled about 21 km. This was our first “wild” canal mooring, and we were unsure of what was permitted. Was it really true that we could just tie up where we wanted to? The canal was completely deserted, with no sign of any authorities to “bid us nay”. The bank was lined with steel shuttering, and we laid Mitch alongside this, threading the mooring ropes through lifting holes burned through the metal.

The canal was bordered with trees, slightly gloomy in the gathering dusk, and a cold wind was blowing along it. After a while, we let go and turned the boat around so it was head to wind, made dinner, and enjoyed the strange sensation of being in rural France in a boat designed for sea angling. The night was cold and windy, but we were warm enough in our cockpit tent. In the morning we enjoyed a walk past fruit farms, before setting off at nine through beautiful countryside, the canal sometimes approaching the Garonne river. We stopped and went shopping in a small épicerie at Fourques. This section of the canal, which passes through hilly country, is rendered level by terracing it above the River Garonne, and as we walked into the town we enjoyed the sight of the boat in the embanked canal, several feet higher than the road. Later, the main engine overheated due to a blocked – I was going to say “sea water suction” but of course the engine was sucking in fresh water, so I suppose “raw water suction” filter is more correct. We hung onto the branches of an overhanging oak tree while I poked vigorously at the weed and mud packed into the skin fitting and pipe, eventually clearing it. For the first time, we tried using our 6 bhp Tohatsu outboard. This was successful, and pushed us along just shy of the 8 kph speed limit, though the boat, with no propwash over the rudder, required a good deal of attention to the steering. It certainly saved the main engine from spending long hours at tickover.

We stopped for the night on the waiting pontoon for the Ecluse de l’Auvignon at the edge of a large field, with carefully tended plums growing under nets. We went into the lock on 6th May 2019 at nine, and tied up briefly to the bank at Sérignac-sur-Garonne, where we thought we might be able to leave Mitch for a few weeks while we returned to England. The telephone number listed in the port was not answered, and so we walked to the tourist office in the town. This was closed, but the walk was delightful, with beautiful perfumed flowers growing along the street.

We crossed the magnificent 539 metre long aqueduct over the Garonne, which with its sister over the Tarn near Moissac, were described by LTC Rolt as “without any doubt the greatest works of civil engineering on the water route between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic”, and entered Agen. We were rather anxious as we entered the large basin outside the railway yards, as we were having second thoughts about the wisdom of trusting to luck that we would be able to find somewhere to leave the boat. We tied up at the Locaboat pontoon and enquired in the office if we could leave the boat there. They could not have been more helpful, and we secured Mitch on one of their pontoons and made our way back to Brittany by train.

We had left the car in Foleux only nine days before, but we had experienced so much in that short time that it seemed in the distant, half remembered past. The Viliane, Biscay and its islands, the Pertuis Breton, the Basque Roads, the Gironde and the vineyards of Paulliac, the trip through Bordeaux and up the Garonne, and then the canal through some of the most rural parts of France.

The next episode is a difficult story to tell, and I think I will deal with it by quoting from my rather sparse log entries:

23rd May 2019 – 19:00: joined Mitch at Agen via C’Berg, Paris, Bordeaux

24th May 2019 – 12:40: dept Agen

14:00: Sally fell into canal – broke arm

15:00: Return to Agen – pompiers

In retrospect perhaps this is not enough, and I should say to anyone working through the French canals: Be very careful on the lock waiting pontoons, they are often very slippery. Try and avoid as far as possible getting on and off the boat – work the ship from the ship as much as you can. Above all, do not rush. I would also like to say how grateful we are to the Locaboat staff at Agen, whose assistance made a great difference to us, and also to the pompiers whose base is near to the canal in Agen, and indeed all of the many people who helped in Agen and on our way home.

It was not until the end of July that Sally was recovered sufficiently to make further progress possible, and even then, her right arm was weak and painful. On 24th July 2019, after an unrestful night with young people congregating around a park bench near the boat, we cast off the piquets we had set into the bank, several months before, and set off again on the canal.

We negotiated the first lock after Agen successfully, and proceeded slowly and carefully along the canal, with the countryside becoming flatter, the fields often filled with maize or sunflowers, and the canal running alongside its nemesis, the Chemin de Fer du Midi.

We tied up for the night alongside the bank near the impressive Golfech nuclear power station, which has its own canal for cooling water.

On 22nd July we continued along the canal, which runs very near to the Garonne river. The weather was very hot, and there were an unbelievable number of demoiselles and dragonflies sporting around the boat. Using the outboard, Mitch went slowly past Valence d’Agen, stopping for water at Pommeric, and then through Moissec, where the canal runs through the centre of the town between two high retaining walls made from the characteristic rose red brick of Toulouse. This brick becomes increasingly commonly used as the canal approaches Toulouse, and it is noticeable that the Tarn pont canal just outside Moissec is of brick construction, in contrast with the similar one at Agen, which is stone. The Tarn pont canal survived catastrophic floods in 1930, unlike the nearby railway bridge which was swept away. So strong is the aqueduct, that for two years following this disaster its towing path was used to carry the railway as well as the canal. We stopped for lunch just after the aqueduct, and then went on to spend the night near St Martin Belcasse, where we walked up to the church past fruit orchards, the air still warm and alive with insects.

Montech, where we stopped on the next day to go to the boulangerie, is full of industrial archaeology, including the brick chimney of the former paper factory, and the Montech Water Slope, where we saw the two diesel locomotives which were employed drive a “wedge” of water on which barges floated up an inclined plane, a short lived but interesting experiment to bypass the locks. In the afternoon, the temperature was 40.5oC in the wheelhouse. Later in the day, we started to get into what were really the outskirts of Toulouse, and we stopped in the evening of 23rd July at the Ecluse d’ Emballens near a huge industrial estate. Nevertheless, the canal itself was insulated from the outside world, and we spent a reasonable night there.

In the morning, 24th July, we realised that we really needed a rest day before tackling the twelve locks between our present location and any potential stopping place on the other side of Toulouse, especially as it was very hot. Accordingly, we made our way back along the canal, stopping briefly at Dieupental to buy vegetables at a market, before mooring to the bank about a kilometre further along. The heat was very intense, as demonstrated by the head of the hammer flying off the shrunken handle when we drove the mooring stakes into the bank. We followed the shade as the day wore on, and moored the boat on the right bank, cooling ourselves off with copious quantities of canal water, and spent a peaceful day, marvelling at the number of insects.

25th July was a big day for us, with the prospect of going through twelve locks before we came to a likely stopping place on the other side of Toulouse, the most we had done in a day, and in very hot weather. We set out early, and it became increasingly urban as we headed towards Toulouse.

It was very hard work in the high temperatures, and we got through a good deal of drinking water, but we made steady progress. We passed the passarelle that carries rugby fans over the canal to the stadium on match days, and by 1230 we were through Ecluse 1, Lalande,

And then into the Port de l’Embouchure, the junction between the Canal du Midi and the Garonne Canal, and where the short Canal de Brienne feeds water from the Garonne River into the Garonne Canal. It was an amazing experience to take Mitch on a loop around the brick walled Port de l’Embouchure, which is surrounded by busy city traffic. We entered the Canal du Midi under the span of a bridge whose shared abutment with the bridge over the Canal de Brienne features an enormous marble bas relief which is said to symbolise the union between the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

The journey through the busy city of Toulouse on a Mitchell Sea Angler was a unique and to use an overworked word, surreal experience. The VNF took our particulars at the Bernais Lock. We did not understand that the locks on this stretch of the canal operate automatically, and we struggled to find a place to put Sally ashore at the next lock, Minimes.

This struggle reached its climax at the Bayard lock, which is very deep as it replaced a three lock staircase. I think we were a bit bemused by the unfamiliar surroundings, and perhaps rather tired, and we were not at all prepared as we entered what we later called the “Gates of Hell”. I had not prepared the lines, and we spent an anxious few minutes in a very dark tunnel sorting them out. Sally went ashore by a not very obvious route, and I took the boat into the lock when the gates opened, making fast to a floating bollard. As the boat rose, I was treated to an astonishing sight, as we seemed to be in the middle of a building site, which in turn was in the forecourt of the huge Toulouse Matabiau railway station, and surrounded by busy roads with people with suitcases in tow, hurrying to and from the station, and nobody taking the slightest notice of us.

We motored slowly through France’s fourth largest city, the canal at first bordered by concrete underpasses with the roadways below the level of the canal. We had a near collision with a reversing and unobservant excursion boat in the broad expanse of Port Saint Sauveur, and then the canal again became tree lined, passing through the university grounds, with the buildings of aerospace companies ever present.

We stopped at Ramonville, on the south-eastern edge of Toulouse, where we decided to leave Mitch while we returned to England. Formalities completed, we outboarded further up the canal to find a spare bit of bank to tie up to for the night. In the evening we walked to the next lock, at Castanet, to see how we would tackle it when the time came. This is good practice when joining a new canal, as the locks vary between waterways, and it allows for the formulation of a plan, rather than turning up in the boat and improvising.

We found that the lock at Castanet is of the traditional Midi pattern, with arched walls. The Canal du Midi is a summit canal, and between Toulouse and the Mediterranean it has to climb over, and then descend from, a height of 190 m above sea level. The canal, completed in 1681, was almost the first summit level canal, preceded only by the much smaller Briaire canal, finished a few years earlier. This meant that the visionary behind the construction of the Canal du Midi, Pierre Paul Ricquet, and his engineer, Francois Andreossey, were working almost without precedent, and they were clearly concerned that straight lock sides might succumb to the pressure of the earth behind them, and so they made the locks with arched sides.

The main problem which Riquet had to overcome was the supply of water to the summit. Previous schemes for a canal between the two seas had envisaged canalising and diverting rivers, but Riquet’s breakthrough was to realise that a copious supply of water could be obtained through a series of reservoirs and channels following the contours of the land from the Montagne Noir near the town of Revel to the watershed at Naurouze.

The following morning, we went into Port Sud, tidied up, and painted the cockpit boards. It was raining heavily, and we decided to spend the night in a rather upmarket hotel a few miles away. We walked there, arriving rather wet and tired, slightly depressed to find the restaurant full, but revived after buying food at a (fairly) nearby supermarket and swimming in the outdoor pool.

We went home by train and ferry via Toulouse, Bordeaux, Paris and Cherbourg, the railway as far as Bordeaux following the line of canal and river. Sally’s arm, while still painful and weak, was improving, and she had resolutely stood up to the rigours of the trip.

We returned on 8th September 2019. We spent the night before joining Mitch in a hotel near the “Gates of Hell” lock outside Toulouse Matabiau railway station, the noise of the water spilling through the lock gates very noticeable in our room. The Port Sud Capitainerie was closed, and as they had the key, we had to hotwire the engine so that we could make our way out of the marina and into Castanets lock. We tied up to the bank just beyond the lock, and spent the night there.

In the morning we walked back to Port Sud and collected the key, and then made our way along the canal, sharing a couple of locks with an English narrowboat. We left Ecluse Gardouch ahead of the narrowboat, and proceeded under outboard. As Sally piloted Mitch round the ninety degree bend at Villefranche, the narrowboat overtook, heeling violently as it negotiated the corner, and driving us almost onto a partly submerged jetty. This was the most ill-judged and aggressive example of boat handling that we experienced on the waterways of France, and Sally with some difficulty dissuaded me from cranking up the IVECO, catching the narrowboat up and giving them a piece of our mind.

We spent the night of 9th September near the town of Baziege. It was raining, and so we walked through a tunnel under the ever present Autoroute au Deux Mers and into the town, and caught the train to Toulouse, spending an enjoyable day sightseeing in that remarkable city.

On 11th September we departed Baziege and continued along the wonderful, tree lined canal. We took on water at Negra, and tied up for the night near the little aqueduct that carries the canal over the River Hers. This was an idyllic mooring, and we watched otters swimming between the banks of the canal.

We left early the next morning, using the outboard all day, except for entering and leaving locks. We waited for the hotel barge Surcouf to overtake us at the Renneville lock

and, in one of our most unusual experiences, stopped at Port Laugrais Sud, which conveniently has a motorway service station attached to it. We tied up opposite the restaurant, and had a rather arduous time of it carrying petrol from the service station to the boat.

We were now nearing the summit of the canal, but our passage through the Ocean lock at the western end of the summit pound was delayed by a fault in the control system. Mitch was now 190 metres above sea level.

We inspected the Naourouze feeder, and then proceeded along the summit pound, and went through the Mediterranee Lock, our first experience of “going downhill”. This was much easier, as there was no need to put Sally ashore, and throwing lines was a thing of the past. Down the double lock at Roc we went, and then the triple staircase of Laurens, where we had our first sight of the snow capped peaks of the Pyrenees, far to the south, before stopping for the night near the Domerqe lock, once kept by M le Croix, who is acknowledged as a reference in L T C Rolt’s seminal book on the Canal, “From Sea to Sea".

The next day, we passed through the La Planque lock, the Pyrenees in sight, and entered the port of Castelnaudary, where we met the highly competent and energetic Capitaine, Odile, who in her youth had abandoned the backwater of Paris to become a resident of Swanagged to leave the boat at Castelnaudary, but in the evening went back along the canal in the dark and tied up for the night at La Planque.

In the morning we snugged the boat down for the winter at Castelnaudary, and returned to England by train and ferry.

Comments