FRENCH WATERWAYS IN THE WORLD'S MOST UNSUITABLE CANAL BOAT: MITCH TO THE MED AND BACK. PART 5 - HOMPS TO SALT WATER

- Paul Weston

- Sep 11, 2025

- 6 min read

From July 2020 to June 2021, during the second Covid lockdown, Mitch lay alongside the bank of the Canal du Midi, at Homps, a small town at the heart of the Minervois wine growing region. I took three months leave from my job, Sally resigned from her temporary one, and we travelled to Homps via Santander. It was quite an exciting ride on the Brittany Ferry Pont Aven, as it went through the Passage du Fromveur, a narrow rocky channel with extreme tides between Ushant and the mainland, through which I would never have taken a yacht. We stayed for a night in a hotel in the lovely Biscay town of St Jean de Luz before proceeding on to Homps.

On the evening of the 15th June 2021, we arrived at Mitch, feeling rather anxious. The anxiety had two causes, a near miss when a car overtook us in the face of oncoming traffic, and concern about the state of the boat. With some trepidation, we lifted up the engine cover and peered into the bilges – dry! The engine started immediately – hooray! We had booked into the local holiday camp, but after checking in, decided it was not for us, and moved into the agreeable Jardin de Homps Hotel for the night.

After breakfast we loaded the boat, and took Mitch down the canal into the town, where we filled the water tanks and cleaned the tent off as much as we could. After shopping in La Redorte, we settled down for our first night on Mitch, only to be rudely interrupted by the scurrying of a mouse, which fortunately for all parties soon succumbed to the temptation of food in a humane mouse trap and was put ashore.

We set off along the canal in the afternoon of 17th June, and at half past five went through the Argens Lock and into the long pound of the canal, which, being without locks, sinuously follows the contour of the topography on the north slope of the Aude Valley. We stopped for the night alongside the bank at the bend in the canal near Paraza, and walked along the towing path to inspect the aqueduct which carries the canal over the Torrent de Repudre. According to the plaque above the structure’s keystone, this was the first Pont Canal, the invention of P P Riquet, built in 1676.

We used the outboard all the next day, traversing the Pont Canal de la Repudre, stopping for lunch near the Pont Pigasse, which displays the armorial symbol of Languedoc. We proceeded on, through the low bridge at La Somail, over the Pont Canal de la Cesse and into La Robine, where we unsuccessfully tried to buy diesel.

The Pont Canal de la Cesse is one of many aqueducts constructed in a scheme of improvements devised in 1686 by the famous engineer Sebastian Vauban to overcome the silting which threatened the Canal’s very existence. We were by now very close to the Mediterranean, and could have proceeded to the sea via the Canal de la Junction which gives access to the ancient Canal de Robine and the Mediterranean via Narbonne.

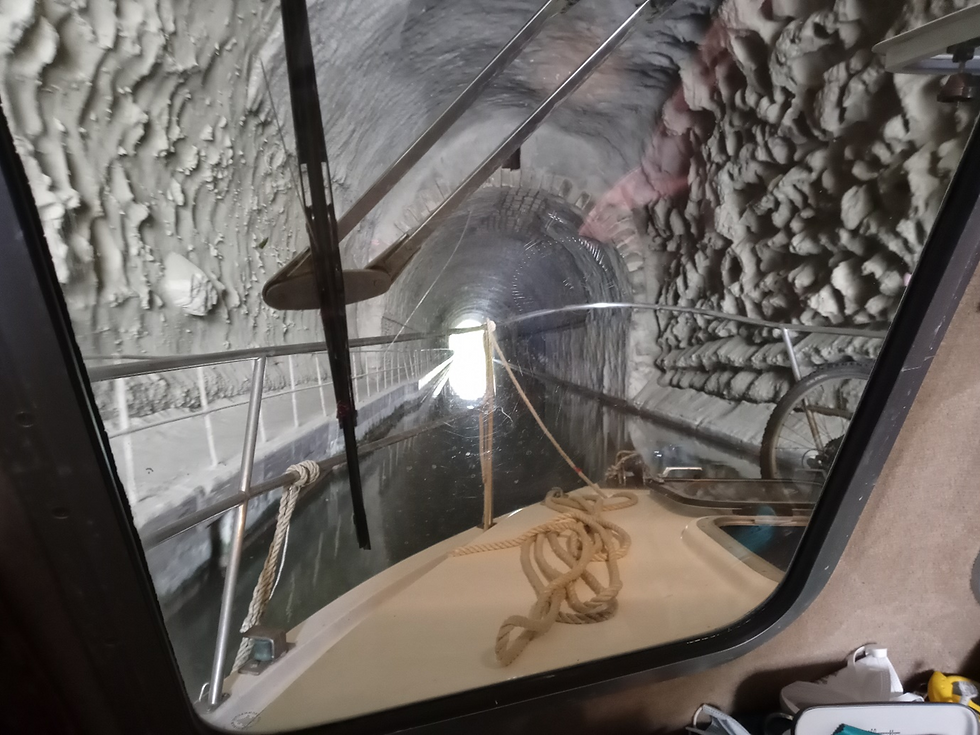

In the evening of the 18th June, we came to the famous Malpas Tunnel. By the time the Canal du Midi had advanced this far, Riquet was beset by enemies, some of whom had the ear of the Sun King’s minister, Colbert, hitherto Riquet’s stalwart supporter. It was held to be impossible that the canal could overcome the Enserune Ridge, near the end of the long pound, and that no more money should be spent on Riquet’s vanity project. Funding became more difficult, and Riquet personally financed much of the last part of the canal construction. The ridge was overcome in triumphant fashion, by driving a tunnel, the first tunnel to carry a navigable waterway, through the soft white limestone of the ridge. The Canal du Midi - the first large summit canal - was of huge strategic importance to France. My book, 'Gulf of Lions', features an attempted British attack on the Malpas Tunnel

We stopped for the night at the eastern end of the tunnel, and walked up to the Oppidium of Enserune, a Gallic settlement perched high on the ridge, with a wonderful view of the surrounding countryside, including the strange and impressive Etang de Montardy, now flat farmland, but formerly a shallow lake which was drained in the thirteenth century by means of a central sump, feeding into a culvert driven through the ridge, 15 metres below Riquet’s tunnel.

The Canal originally made use of a stretch of the river Orb, which it joined at Beziers. The Orb is considerably lower than the long pound, and the Canal must descend a steep slope to the river’s level. That Riquet might fail to overcome this obstacle was the last hope of his enemies, but they were confounded in spectacular fashion by the construction of the famous Fonserannes staircase, originally of nine locks. The view of Beziers from the head of the staircase was magnificent, and we descended in company with several hire boats, with no drama.

We tied Mitch up at the foot of the staircase, just before the magnificent aqueduct constructed by Victorian engineers to carry the canal over the Orb, and walked into Beziers. We saw the disused locks which, before the construction of the aqueduct, connected the canal to the Orb. Beziers, said to be the oldest town in France, was the site of a particularly grotesque massacre during the Albigensian Crusade in 1209, when the entire population was killed, and the town destroyed.

We continued across the pont canal over the Orb, stopped for shopping and lunch at Villeneuve les Beziers, and then, thankfully, for our tanks were almost dry, for fuel and water at the very friendly Le Boat hire base at Port Cassafieres. We spent the night alongside the canal bank a little further on, and in the evening walked the short distance to the beach and our first swim in the Mediterranean.

Our night’s sleep was disturbed by the crashing of heavy animals in the undergrowth of the bank, and we decided that they were probably wild boars.

The next day, 20th June, we continued in heavy rain, past a forlorn looking amusement park, and through the Libron barrage, which protects the canal in the event of flooding from the Libron river, and into the famous round lock at Agde, which connects the canal to the river Herault, and hence to the sea. We kept straight on, and soon came to the point where the canal makes use of a short stretch of the Herault, before continuing along its man made channel.

The Herault seemed so enticing, broad, blue and tree lined, that we decided to continue along the river, rather than turning into the canal, and ran up the river with the engine turning at an exciting 1200 rpm. We made fast to a pontoon at Bessan and walked into the town, quiet and historic, and then moved Mitch down the river, making fast to trees on the bank for the night. The river, though prone to violent floods, was extremely peaceful, alive with insects, fish and birds.

21st June 2021 was to be our last day on the Canal du Midi. We cast off from the trees on the bank of the Herault, and made our way downriver, re-entering the canal before passing through Bagnas lock, the last one on the Canal.

After the lock, the canal passed through low lying, marshy country, and before we knew it, we were passing the lighthouse of Onglous, and Mitch was in salt water, not exactly the sea, but the Etang de Thau. Perhaps because of the sudden absence of canal banks, to which we had become so accustomed, I became completely disorientated, and could not decide which way I should point Mitch’s head.

We were rescued by Raymarine, which showed no signs of confusion. We slowed down to a crawl, put in a couple of waypoints, engaged the autopilot, and away we went, gradually acclimatising ourselves to the expanse of salt water. I gradually opened up the engine, and Mitch came alive, bashing through the short chop in the Etang in fine style, as though saying “this is what I was made for!”.

Comments